OOP in Python

Classes and objects

Here’s the simplest possible class

class Foo: pass

When we “call” a class, we instantiate it, returning an object of type Foo (also known as class instance):

> foo = Foo()

> type(foo)

<class '__main__.Foo'>

Classes and objects (2)

In Python, everything is an object. Try for instance:

- type(int): built-in types

- type(Foo): classes

- type(foo): instances of classes

- type(ValueError): exceptions

- type((_ for _ in range(10))): other built-in types, like generators

- type(lambda x: 2*x): functions

Classes have members

Class members are either:

- Atributes - properties stored in the class or its instances

- Methods - functions associated to the class or its instances

> foo = Foo()

> dir(foo) # inspects an object members

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__',

'__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__',

...]

We haven’t defined any attributes or methods and yet our class already has many…

Classes have members (2)

All Python (3+) classes implicitly inherit from object:

> o = object()

> dir(o)

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__',

'__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__',

'__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__',

'__new__', '__str__', ...']

- __repr__: called when doing print(o)

- __str__: called when str(o)

- __hash__: called when hash(o)

- __eq__: called when o == “a”

- …

Defining class and instance attributes

class MLModel:

# this is a class attribute

name = "MLModel"

# this is the class constructor

def __init__(self, parameters):

# example instance attribute

self.parameters = parameters

Defining class and instance attributes (2)

# When we call the class, it internally executes

# the __init__ method (constructor)

> ml_model = MLModel([1, 2, 3])

# we access the instance attribute

> ml_model.parameters

[1, 2, 3]

# class attributes are also accessible from the instance:

> ml_model.name

Defining instance methods

Instance methods are functions defined on the instances of a class. They must take the instance as an input, together with any other arguments

import pickle

class MLModel:

def __init__(self, parameters):

self.parameters = parameters

def save_parameters(self, path):

"""

Saves the model parameters into a file names `path`

"""

with open(path, 'wb') as f:

pickle.dump(f, self.parameters)

Defining instance methods (2)

> ml_model = MLModel([1, 2, 3])

# When we call an instance method, the `self`

# parameter is passed implicitly

> ml_model.save_parameters('model.pkl')

Defining instance methods (3)

Warning

Class members are mutable!

> ml_model = MLModel([1, 2, 3])

# we can freely override paremeters

> ml_model.parameters = "whatever"

# or even define new methods and attach them to the instance

> ml_models.new_method = lambda x: 2*x

@property decorators are a way to make sure setting attributes is disabled or doesn’t break things

Defining class methods

Class methods apply to the class, not the object. They are useful for things like factory methods

class MLModel:

....

@classmethod

def load(cls, saved_parameters_path):

"""

Returns an instance of `MLModel` from the parameters saved via

`MLModel.save_parameters`

"""

with open(saved_parameters_path, 'rb') as f:

parameters = pickle.load(f)

return cls(parameters)

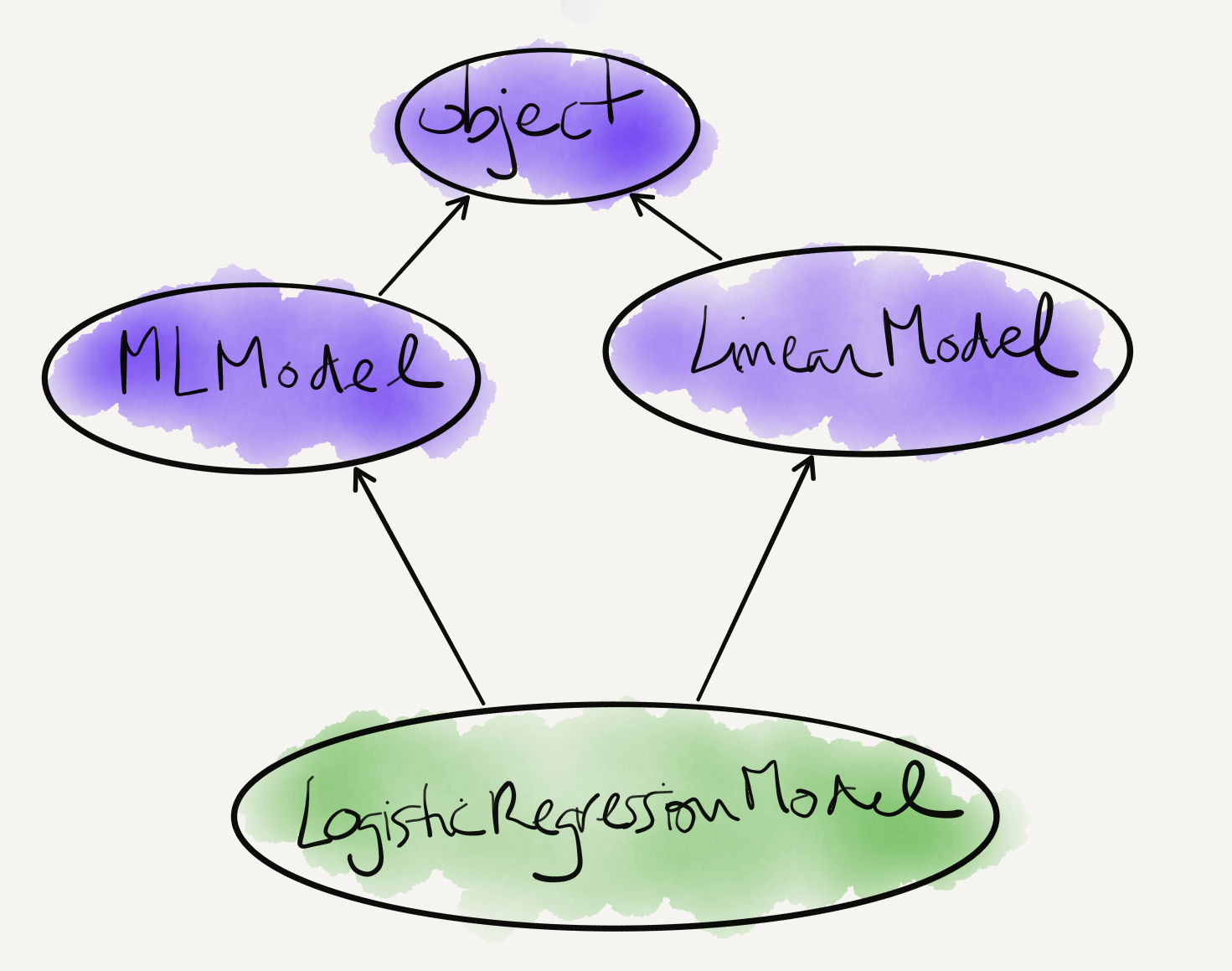

Inheritance

Classes can inherit from classes other than object:

class LogisticRegressionModel(MLModel):

def __init__(self, parameters):

# This calls LogisticRegressionModel's superclass constructor.

# It is equivalent to MLModel.__init__(self, parameters) but preferred,

# because it avoids hard-coding the parent class name

super().__init__(parameters)

def predict(self, x):

...

Now every instance of LogisticRegressionModel has a save_parameters method inherited from MLModel, and the LogisticRegressionModel class has a load method.

Multiple Inheritance

import numpy as np

class LinearModel:

def __init__(self, coefficients):

self.coefficients = coefficients

def predict(self, x):

assert x.shape[1] == self.coefficients.shape[0]

return np.dot(x, self.coefficients)

class LogisticRegressionModel(MLModel, LinearModel):

def __init__(self, parameters):

super().__init__(parameters)

# We also need to call the constructor for `LinearModel`!

super(MLModel, self).__init__(parameters)

def predict(self, x):

x_times_coef = super().predict(x)

return sigmoid(x_times_coef)

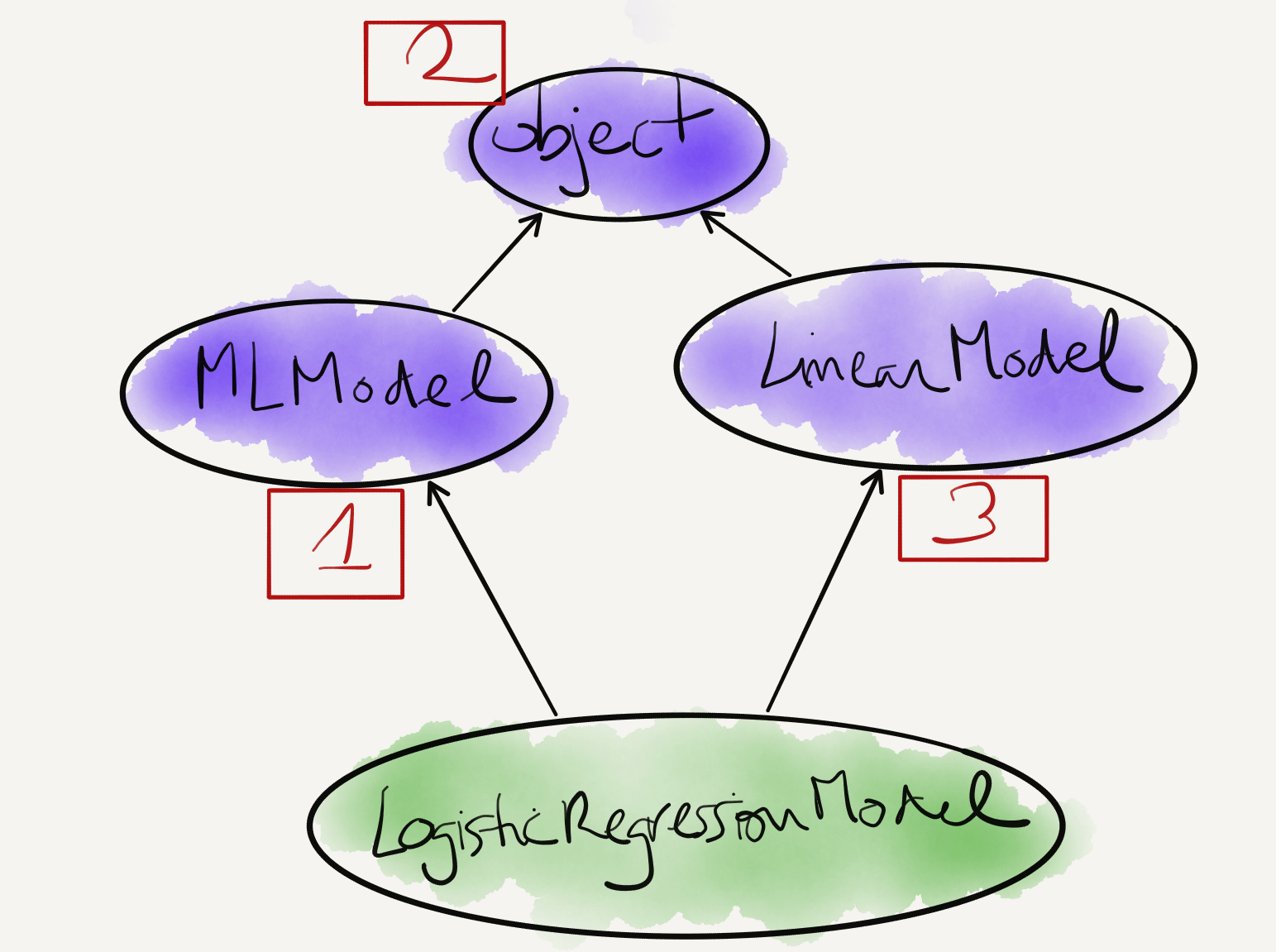

Multiple Inheritance (2)

When we run super().__init__(parameters), which of the 2 parent classes’ __init__ do we run?

Multiple Inheritance (3)

Multiple inheritance is tricky, particularly when we have diamond inheritance or methods with the same name:

- Python implements a method resolution order (mro)

- It can be summarized as depth-first, left to right (source)

- You can inspect a class’ mro by looking at its .__mro__ attribute

> LogisticRegressionModel.mro()

[<class '__main__.LogisticRegressionModel'>, <class '__main__.MLModel'>, <class '__main__.LinearModel'>, <class 'object'>]

More on super: Super considered super

Multiple Inheritance (4)

When we run super().__init__(parameters), we will run MLModel.__init__

Mixin classes

Mix-in classes are designed to be used with multiple inheritance:

- They provide specific functionality to derived classes.

- It is recommended that:

- they include a super().__init__ call in their constructor and that

- they are used first in the subclasses

Mixin classes (2)

class ModelSavingMixin:

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

def save_parameters(self, path):

with open(path, 'wb') as f:

# this will fail unless `parameters` exist!

pickle.dump(f, self.parameters)

@classmethod

def load(cls, saved_parameters_path):

with open(saved_parameters_path, 'rb') as f:

parameters = pickle.load(f)

return cls(parameters)

Mixin classes (3)

class LogisticRegressionModel(ModelSavingMixin, LinearModel):

def __init__(self, parameters):

super().__init__(parameters)

# No longer need to call the constructor for `LinearModel`!

def predict(self, x):

x_times_coef = super().predict(x)

return sigmoid(x_times_coef)

The LogisticRegressionModel now has saving and loading functionality inherited from ModelSavingMixin

Mixin classes (4)

We still have a problem…

class ModelSavingMixin:

...

def save_parameters(self, path):

with open(path, 'wb') as f:

# this will fail unless `parameters` exist!

pickle.dump(f, self.parameters)

Some models may have a vector of parameters, others are parameterized otherwise…. How can we make this more generic so that it can be reused?

Abstract classes and interfaces

The latter is a good reason to define the mix-in as an abstract class:

class AbstractModelSavingMixin:

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

def get_parameters(self):

raise NotImplementedError

def save_parameters(self, path):

with open(path, 'wb') as f:

# this will fail unless we override self.get_parameters()

pickle.dump(f, self.get_parameters())

@classmethod

def load(cls, saved_parameters_path):

with open(saved_parameters_path, 'rb') as f:

parameters = pickle.load(f)

return cls(parameters)

Abstract classes and interfaces (2)

For now the only thing that makes the class abstract is its name and the unimplemented get_parameters()…

The abc (abstract base classes) library is useful to make it more like a regular abstract class:

Abstract classes and interfaces (3)

import abc

# inherits from abc.ABC, which internally sets a `meta_class`

# cf: https://realpython.com/python-metaclasses/

class AbstractModelSavingMixin(abc.ABC):

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

@abc.abstractmethod

def get_parameters(self):

"""Retrieves the parameters of the model as a pickable object"""

def save_parameters(self, path):

with open(path, 'wb') as f:

# this will fail unless we override self.get_parameters()

pickle.dump(f, self.get_parameters())

...

Abstract classes and interfaces (4)

And now we just need to implement the get_parameters method in its subclasses:

class LogisticRegressionModel(ModelSavingMixin, LinearModel):

def __init__(self, parameters):

super().__init__(parameters)

def get_parameters(self):

# the implementation could vary depending on the model.

return self.parameters

def predict(self, x):

x_times_coef = super().predict(x)

return sigmoid(x_times_coef)

> model = LogisticRegressionModel(np.ones(3))

> model.save_parameters('model.tmp')

> loaded_model = LogisticRegressionModel.load('model.tmp')

Abstract classes and interfaces (5)

Any class subclassing AbstractModelSavingMixin will:

- Not be instantiable unless it defines get_parameters

- Return the expected issubclass and isinstance behavior:

> model = LogisticRegressionModel(np.ones(3))

> issubclass(LogisticRegressionModel, AbstractModelSavingMixin)

> isinstance(model, AbstractModelSavingMixin)

More info: Abstract Base Classes from PyMOTW

Why bother about all of this!?

- Maintainability: Can a new developer understand what is going on?

- Extensibility: How easy is it to add new functionality?

- Testability: How easy is it to unit test each functionality?

Warning

Beware of building abstractions for problems we don’t yet understand! It’s often better to start with concrete implementations.

Python’s philosophy: (Dynamic) Duck typing

“If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck”

Practice time

Let’s practice by improving the way we implemented text pre-processing in the capstone project.

1. Take a look at how we apply a text pre-processing in the LocalTextCategorizationDataset class in the preprocessing package and how we instantiate this class in the train module.

- What are the problems of this approach?

3. Let’s think and implement a design that: (1) Ensures the function we pass to the LocalTextCategorizationDataset constructor abides by an expected interface, and (2) Enables other developers to build other pre-processing implementations that will work

Packaging in Python

Modules

A Python “module” is a single namespace, with a collection of values:

- functions

- constants

- class definitions

# hello_world.py

hello_str = "hello {}"

def hello(name): return hello_str.format(name)

> from hello_world import hello

> hello("arnau")

Packages

A package is a directory with a file called __init__.py and any number of modules or other package directories:

greetings

__init__.py

hello_world.py

spanish

__init__.py

hola_mundo.py

The __init__.py file can be empty or have code in it, it will be run when the package is imported (import greetings)

Packages (2)

In addition, a python package is usually bundled with:

- Documentation

- Tests

- Top-level scripts

- Data/Resources

- Instructions to build and install it

setuptools

setuptools is an extension to Python’s original packaging tool (distutils) that provides a number of functionalities:

- helpers for installer script

- auto-finding dependencies

- resource management

- develop mode

setuptools (2)

setup.py # this is the installer/build script

greetings

__init__.py

hello_world.py

spanish

__init__.py

hola_mundo.py

# setup.py

import setuptools

setuptools.setup(

name='greetings',

version='0.0.1',

packages=setuptools.find_packages(),

install_requires=['pandas >0.1,<1.0'] # dependencies

python_requires='>=3.6' # python version

)

setuptools (3)

This was just a simple example, setup.py enables a lot more configuration:

- Version & package metadata

- List of other files to include

- List of dependencies

- List of extensions to be compiled

It’s out of the scope of this training but instead of passing arguments to the setuptools.setup function, one can also configure the build via a setup.cfg configuration file.

setuptools (4)

With the setup.py ready, we can:

# build a (source or wheel) distribution

> python setup.py sdist bdist_wheel

# install locally

> python setup.py install

# or

> pip install .

# or install in develop/editable mode

> python setup.py develop

> pip install -e .

Practice time

1. Create a greetings package with two sub-packages, english and spanish, each containing a simple function to greet in the corresponding language, using the termcolor package to print the greeting in color.

- Write the setup.py script for the package, including the requirement for the termcolor dependency

- Install the package in develop mode (don’t forget to do it in the ml_in_prod environment!)

- Change some of the code and notice how the changes are reflected on the next import, without having to re-install

Other useful Python patterns

decorators

import time

# here de define the decorator, which is a higher-order function

def timeit(f):

def timed_f(*args, **kwargs):

tic = time.time()

val = f(*args, **kwargs)

print(f"Call to {f.__name__} took: {time.time() - tic}")

return val

return timed_f

@timeit

def sum(x, y): return x + y

>>> sum(3,4)

Call to sum took: 3.814697265625e-06

decorators (2)

There are a few built-in decorators:

- @property: to decorate an instance method so that it behaves like an attribute, configure setters/getters

- @classmethod: to define a class method

- @staticmethod: to define a method as static (can be used without instantiation)

And several typical use cases:

- logging

- caching

- implementing re-tries

- registering plugins, etc

iterators

- An object is an iterator if it implements the iterator protocol (__iter__ and __next__ methods)

- if an object implements the iterator protocol… it can be iterated

>>> hello_worlds = HelloWorldIterator(10)

>>> for hello_world in hello_worlds: print(hello_world)

Let’s build a HelloWorldIterator !

iterators (2)

class HelloWorldIterator:

def __init__(self, n):

self.n = n

self.current = 0

def __iter__(self):

# here we could return any object implementing __next__

# for simplicity, we return self which implements __next__ :)

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.current < self.n:

self.current += 1

return "Hello!"

else:

raise StopIteration

iterators (3)

As you can imagine, there are several objects in python with built-in iterators:

- lists

- tuples

- dict

You can check by yourself:

>>> dir(dict()) # or dir({'a': 1})

[.... '__iter__', ....]

>>> dict_iterator = dict().__iter__()

>>> dir(dict_iterator)

[.... '__next__', ....]

generators

The iterator pattern is a bit cumbersome… In many cases we can accomplish the same using the generator pattern:

def hello_world_generator(n):

for _ in range(n):

yield "Hello!"

>>> for hello_world in hello_world_generator(10): print(hello_world)

Or even more succint: using a generator comprehension:

>>> hello_world_generator_2 = ("hello" for _ in range(10))

>>> for hello_world in hello_world_generator_2: print(hello_world)

generators (2)

The most important thing about generators (and some iterators) is that they are lazy-evaluated: that is, their elements are not computed or stored in memory until it is their turn. (Unlike lists, dicts, etc)

Example applications:

- Loading data in chunks that would not fit in memory (deep learning)

- Exploring combinatorial data structures without running out of memory

- Implementing lazily-evaluated data pipelines…